Have you ever been surprised by a question during a meeting and not known how to respond? Or maybe you've sat down to take an exam and, despite studying, you suddenly can't remember a single thing. What's going on?

It turns out that there's a psychological explanation for these types of situations. Information processing theory offers insight into how human brains acquire, process, and store information.

How we process information affects everything from how well we learn to our decision-making methods. Below, we'll explore the basics of information processing, some of the significant models of the theory, and how you can use key insights to enhance your thinking and learning.

Information processing theory is a cognitive psychology model explaining how we receive, process, store, and retrieve information. American cognitive psychologist George A. Miller developed the theory in the 1950s, basing his research on Edward C. Tolman's cognitive maps and latent learning theory.

The information processing theory describes how the human brain works with new information. According to this theory, the brain receives information from the environment, processes it in some way, and then stores it so it can be retrieved for later use.

Some compare this method to a computer, which inputs information (from a keyboard or mouse), processes it (using programs), and produces output (on a screen or printer). However, the human mind is much more complex than that, and human cognitive abilities are much more sophisticated.

Information processing theory has since been expanded and developed into several models. Each model is different and has its own strengths, but they all contain three central components:

These components work together in a multi-stage system to help us take in information, use it, and/or store it for later retrieval and use.

Information processing theory has been influential in cognitive development and educational psychology. It provides a framework for researchers to study learning processes, cognitive abilities, and what occurs when the human brain processes information.

As a result of this research, the theory has been expanded into several models. The Atkinson-Shiffrin and Baddeley-Hitch models are the most noteworthy.

The Atkinson-Shiffrin model was proposed by Richard C. Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin in 1968. Their model, also known as the multi-store model, suggested that information is stored in three separate memory stores:

One of the strengths of the multi-store model is that it provides insight into the structure and function of short-term memory. Consequently, it has served as a solid foundation for further study and memory research.

However, the Atkinson-Shiffrin model is a linear information processing model, implying that information moves in one direction from one stage to another. Researchers have since found that the information processing system doesn't always flow like that. In contrast, parallel processing is possible, and knowledge can move back and forth between different memory stores.

The model also doesn't consider how information is processed within each store. For example, it doesn't explain in detail how information is encoded, how it is retrieved, or how it is forgotten.

The Baddeley-Hitch model, also known as the working memory model, was proposed by Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch in 1974 as a more accurate representation of short-term memory. This updated model splits short-term memory into multiple components rather than treating it as a single unit. The parts of working memory are:

The Baddeley-Hitch model is the most influential information processing model and is supported by a large body of research, helping us better understand how the brain processes information.

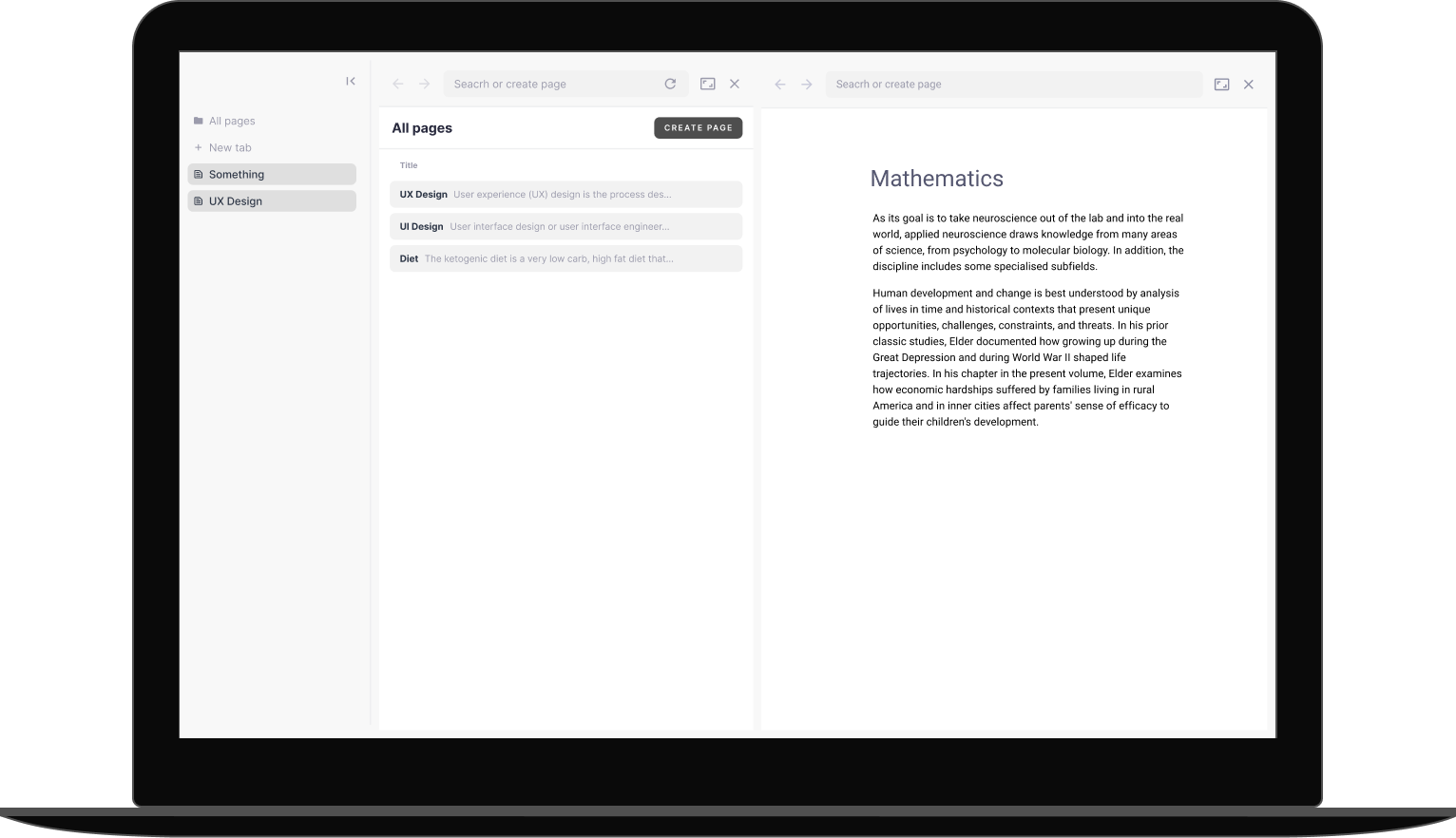

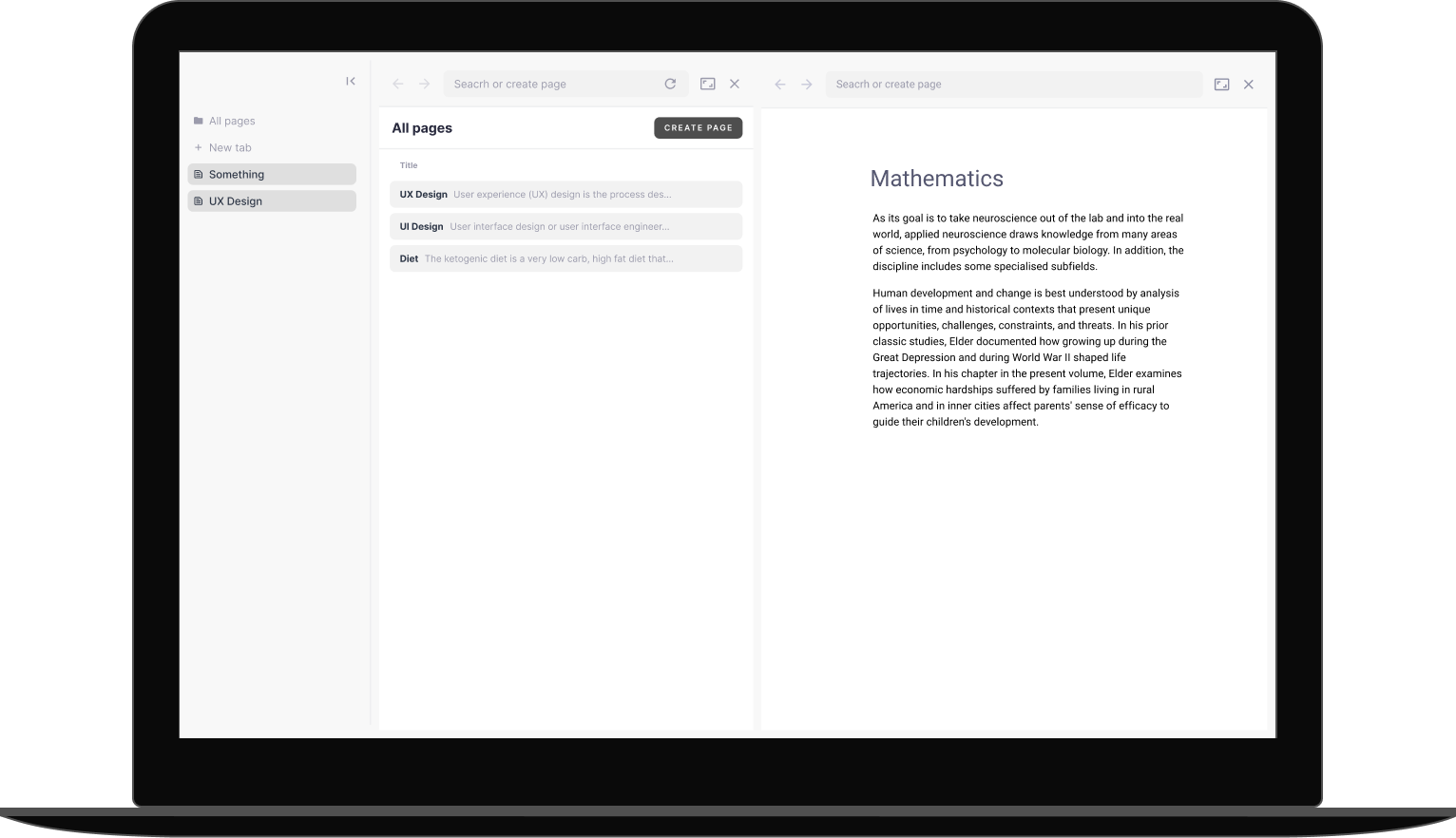

Gather information, take notes, review, reflect, surface insights. All from one perfect, distraction-free interface.

Learn moreUnderstanding information processing theory is helpful for anyone interested in how the human brain works, but the theory also has applications in organizational psychology. Some researchers believe it can be used to improve information processing and problem-solving within organizations.

According to research, information processing in organizations occurs in four stages:

Understanding an organization's information processing approach can help leaders optimize team communication and clarity. When information isn't adequately disseminated throughout a workplace, it leads to uncertainty and increased workloads. However, if enough information is processed, tasks can be understood before they're performed, improving efficiency and reducing risk.

Much like organizations, we can benefit from understanding information processing theory. Knowing how our brain processes information when learning something new allows us to adapt how we approach personal experiences. Here are a few examples of how information processing theory can apply to everyday life:

Miller asserted that human minds could only remember around seven pieces of information at a time (plus or minus two). The number may be even lower, according to more recent research on human memory. When learning something new, like a foreign language or musical instrument, focus on manageable chunks of information. For instance, break down vocabulary words into groups of seven and practice until you can remember all of them before moving on to the next set.

If you're studying for an exam, try using several methods, including listening to the information, reading it, and taking notes. Each learning method uses a different type of working memory, including the visuospatial sketchpad and the phonological loop. You’ll activate all parts of your working memory to increase the chance of encoding in your long-term memory.

Taking breaks is essential to optimize information processing, but the key is knowing how to strategically time them. When choosing your workstyle, consider the type of work you need to do. For example, a cognitive-heavy task may benefit from the flow state rather than the Pomodoro method. On average, it takes 23 minutes to get into flow, so if you followed the Pomodoro method of 25-minute work sessions, you'd interrupt yourself just as you were getting into that deep work zone. The five-minute micro breaks are also too short to allow your brain to rest. However, a series of short tasks would fit this style well..

If an important project requires organizing information, try using mind maps. Mind maps are diagrams that link visual information together, making it easier to see the connections between ideas. Not only is mind mapping helpful when brainstorming or taking notes, but the act of writing and drawing will activate your visuospatial sketchpad. This makes it easier to encode the information. In addition, an essential part of learning occurs when we link new concepts with what we’ve learned or experienced in the past, which occurs during the mapping process.

Multitasking is often touted as a skill, but it can actually lead to information overload. Our short-term memory can only handle a limited amount of information — and on top of that, we suffer from attention residue every time we switch from one task to another. Instead of multitasking, focus your attention on a single task. Working with a smaller amount of information makes it easier to focus and easier to process. As a result, you'll reduce mistakes and increase productivity.

ABLE - the next-level all-in-one knowledge acquisition and productivity tool.

Learn moreInformation processing theory is a cognitive psychology theory that provides a framework for understanding how the human brain acquires, processes, stores, and retrieves information. The theory states that information processing occurs in stages, with each step connecting to information from the previous stage. It has been used to explain various cognitive processes, including working memory, learning theories, and problem-solving.

Understanding how information is processed can help us adapt our behavior to better suit our needs. Whatever your goals are, you can learn something new and improve your productivity by getting familiar with the theory of information processing.

I hope you have enjoyed reading this article. Feel free to share, recommend and connect 🙏

Connect with me on Twitter 👉 https://twitter.com/iamborisv

And follow Able's journey on Twitter: https://twitter.com/meet_able

And subscribe to our newsletter to read more valuable articles before it gets published on our blog.

Now we're building a Discord community of like-minded people, and we would be honoured and delighted to see you there.